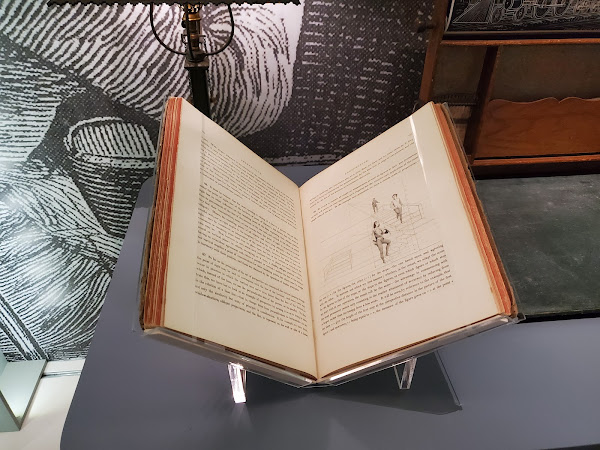

Like an antiquities thief eyeing his next score, I often treat a museum visit as a sort of shopping trip. Instead of looking for my next heist, I'm on the lookout for ideas and inspiration. This last trip to the Smithsonian was no different. One gem I walked away with is featured in this pic:

According to the associated plaque, that's a copy of the The American Drawing Book: Manual for the Amateur, Basis of Study for the Professional Artist by John Gadsby Chapman. Published in 1847, as the title suggests, this text was intended to teach both amateurs and pros how to draw.

Thanks to Google Books we need not admire the text through glass alone. You can download a PDF or read the book online.

I've been making my way through the text, and have spent enough time with it to form an opinion. Like any modern drawing book, the introduction dwells on the many benefits of learning to draw. The 'American' in the title is emphasized in the introduction, because at the time the text was published Europe was the center of the design universe. America had quite a bit of catching up to do, and Chapman intended to assist by providing this text for use by all, from the humble public student to the eager professional.

Among the groups of people he encourages to pick up the pen are women.

There are those, of another class of society, to whom education in Drawing may prove a real blessing whose painful and ill-repaid labors, to earn a scanty provision for themselves and families, have so often called forth our sympathies; and, while public feeling loudly declaims against the evil, no efficient remedy has been applied. Of the thousands of dependent females who are compelled to toil, night as well as day, to the destruction of health and life, and who are often tempted into paths of vice and misery by absolute necessity, how many there are who possess talent that needs but cultivation to secure them both respectability and support. The natural refinement and delicacy of the female mind renders it a fruitful soil, that should not be neglected or let run to waste, when its cultivation might realize such rich advantages, not only to themselves, but to their country. Give them the advantages of education in Drawing ; begin in your public schools let them carry it to their looms, to the manufacture of articles of taste and fancy, to their firesides, to the early education of their children;—-and more, if they possess the talent,—-let them take the pencil, the chisel or the burin. Give them strength, by proper education, to feel what they can accomplish, and we shall soon see the broken-hearted victims of incessant toil worth the wages of men, in departments of industry and usefulness for which they are by nature so well adapted.

Surprisingly woke, no?

I also appreciated his appeal to parents who may consider drawing to be a frivolous waist of time.

Fathers and Teachers--call not your boys idle fellows, when you find them drawing in the sand. Give them chalk and pencil — let them be instructed in design. “But,” you say, “I do not want my boy to become an artist.” Depend upon it, he will plough a straighter furrow, and build a neater and better fence, and the hammer or the axe will fit his hand the better for it: for from it, no matter what may be his calling in life, he will reap advantage. Last, not least, you give him a source of intellectual enjoyment, of which no change of fortune can deprive him, and that may secure his hours of leisure from the baneful influence of low and ignoble pursuits.

While the text may be written in awkward language, I can't think of strong arguments for why someone should learn to master the arts.

Chapman clearly had his advocacy game down. But how about the core of the text? Does the drawing instruction hold up? I'm only part way through the book, but so far, I'd say Chapman is nailing it.

Consider this advice he offers about favoring a pen over a pencil and an eraser:

Let us lay well the foundation, before we begin the structure. He who starts with the black lead pencil in one hand, and the Indian rubber in the other will find, however convenient the latter may be, that he will soon fall into loose and slovenly habit, of which it will be difficult to divest himself. They are both good and serviceable in their places; but too often, in the hands of beginners, most sadly abused.

This mirrors contemporary advice I've read on the topic.

So far, Chapman has focused on drawing progression. I've been faithfully following each of his exercises, which started as simply as tracing lines created with a straightedge. I'm finishing exercise #17 which has me drawing simple objects and using a grid to help navigate where the lines should be placed.

The grid vastly simplifies the drawing process, and I was impressed at Chapman's choice to rely on it. It then occurred to me: what if I wrote some code that let me take any pictures and draw a grid over it? That would be one useful tool, I mused. I could take Chapman's strategy from the 1850's and bring it to my 2022 smartphone! As a precursor to writing the app I had in mind, I searched Google Play for a similar topic. Turns out, there are quite a few apps that do exactly what I had in mind.

Apparently, overlaying a grid on a picture to help draw it is standard practice. Chapman knew this is 1840, and artists know this today. I'll take this as a hint that Chapman's drawing advice is standing the test of time, and more importantly, I have a lot to learn.

Here's a few samples of the work I've completed. I look forward to seeing if Chapman's approach continues to be effective.

No comments:

Post a Comment